Tijdens het schrijven aan mijn lezing over het marxisme, Maarten Luther en de Reformatie, die ik 21 september 2017 gaf aan de Vrije Universiteit en hier onlangs publiceerde (https://wimberkelaar.com/2024/02/18/marxism-martin-luther-and-the-reformation-the-story-of-a-problematic-relationship/), raakte ik weer geïntrigeerd door de vele reformaties die het marxisme kende. Bij het werken aan die lezing viel in een notendop al op hoezeer marxisten in hun interpretatie van de 16e-eeuwse Reformatie hechtten aan de orthodoxie van hun interpretaties. Vrijwel allen die na hen kwamen bewezen op zijn minst lippendienst aan de aartsvaders Karl Marx en Friedrich Engels. De oorzaak was niet slechts gelegen in de kwetsbaarheid van de Duitse Democratische Republiek die in haar veertigjarig bestaan krampachtig zocht naar legitimatie. De hang naar orthodoxie stak dieper. Marx en Engels zelf zetten zich in de 19e eeuw al hevig af tegen de “utopisch socialisten” om hen heen en presenteerden zich als de ware, “wetenschappelijke” socialisten. Ik besloot me destijds nog eens te verdiepen in het ingewikkelde begrip ‘reformatie’, maar dan reformatie binnen het marxisme, met onderstaand artikel als resultaat. Wederom in het Engels geschreven en bedoeld voor de nimmer verschenen en vermoedelijk nooit te verschijnen bundel over het Reformatie-begrip bij uitgeverij Brill.

Friedrich Engels ‘explanation’ (and reformation) of Marxism

The struggle of Marx and Engels to obtain hegemony for their historical materialism above the so-called (forms of) ‘utopian Socialism’ has been well documented. Marx and Engels tried to distinguish themselves from other Socialists whom they called ‘utopian Socialists’. Not immediately, but after being deeply influenced by critics of emergent capitalism such as Claude Henri de Saint Simon, Charles Fourier and Pierre Joseph Proudhon. Initially, these French critics were of help during the phase that Marx, in his Paris years in the 1840s, went from critique of religion to critique of society. But there was an essential difference, as Leszek Kolakowski has argued: the ‘utopian Socialists’ were not revolutionaries like Marx and Engels. They were never convinced that political changes in themselves could bring about the new economic order and the redistribution of wealth. They believed that economic reforms must be achieved by economic action and they rejected the prospect of revolution. Whereas for the three ‘utopists’ poverty was the main issue, for Marx it was alienation.

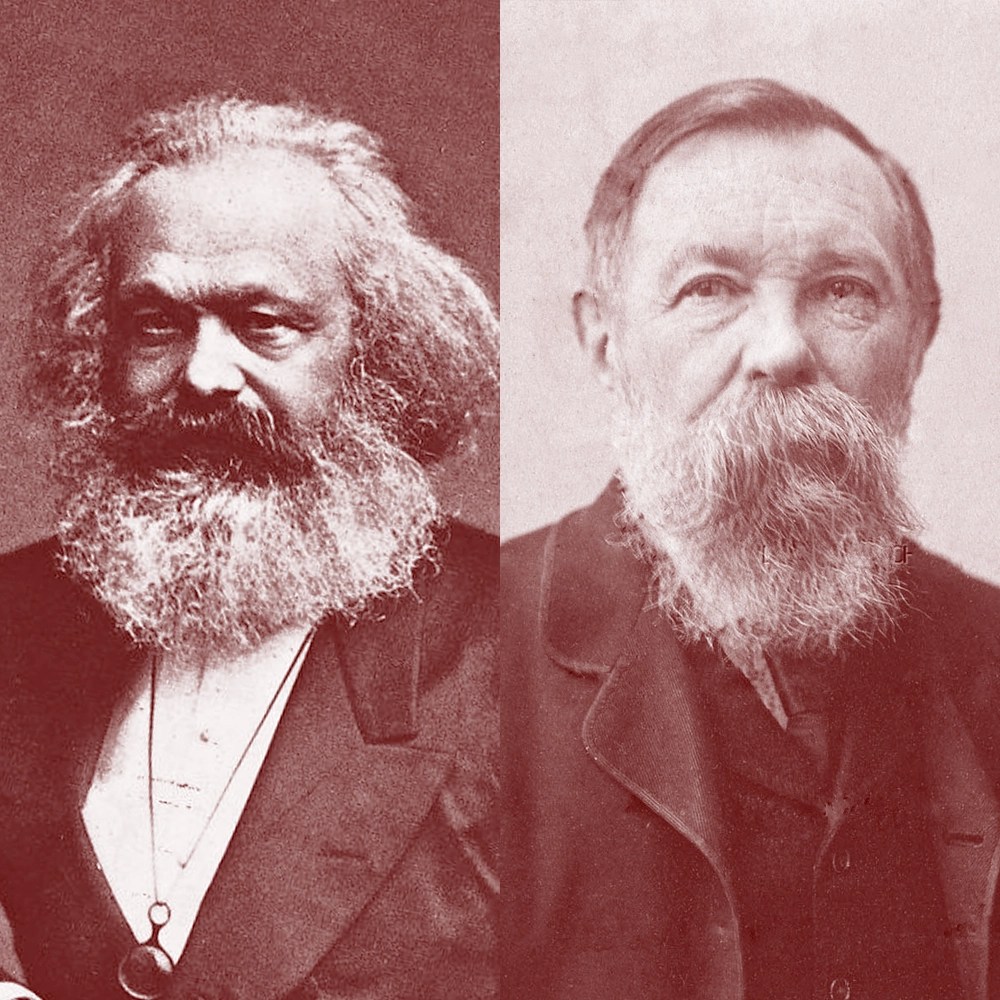

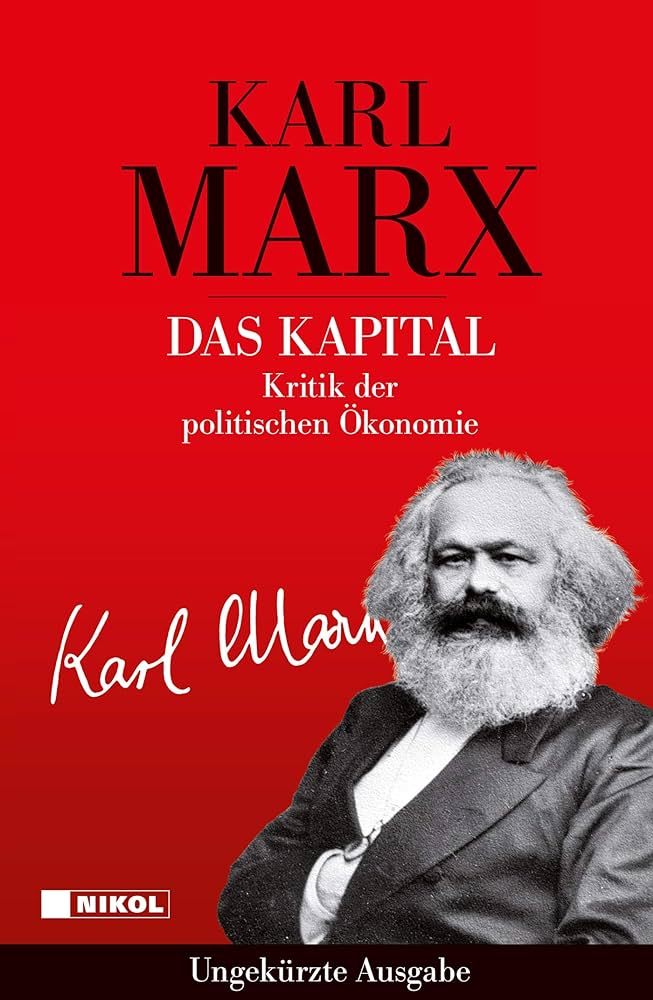

Marx however was never exclusively an ethical thinker who believed that revolution was necessary from a normative point of view. Nor was he a historical determinist who thought that revolution would be the necessary outcome of social developments. He balanced the two and that gave his work its tension and exposure. Although there were incitements to scientism in Marx’ work (especially in Capital), it was Engels who tried to establish ‘Marxism’ as a scientific current. At Marx’ funeral on March 17, 1883 in London, he said: ‘Just as Darwin discovered the law of development of organic nature, so Marx discovered the law of the development of human history. He was a man of science’. But even before that, Engels had tried to disassociate Marxism from its predecessors in The Development of Socialism from Utopia to Science (1880).

He paid tribute to their merits, proclaiming that the utopian Socialists, to which, according to Engels, Robert Owen also belonged, were representatives of the nineteenth-century pursuit to deal with the upcoming Industrial Revolution. However, they acted not as representatives of a class but were committed to mankind as a whole. They had no adequate answers to the problems which were the result of Industrial Capitalism. But rather than to ridicule their ‘stupendous’ forms of ‘Socialism’, Engels honored their sometimes ‘grand thoughts and germs of thought’.

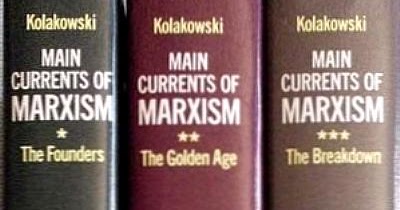

Nevertheless, all this praise was a prelude to the observation that they were obsolete thanks to the appearance of Marx who ‘discovered’ not only the materialistic conception of history but also the revelation of the secret of capitalistic production through surplus-value. Engels changed and solidified Marx’ work in Marxism and gave it the authority of an orthodoxy. Changed, because Engels developed his Marxism in a dialectical philosophy of nature in complement of Marx’ fragmented work. Leszek Kolakowski (image), the eminent Polish connoisseur of Marxism, has made the differences between Marx and Engels clear in his excellent Main currents of Marxism: ‘According to Marx, nature was not something ready-made and assimilated by man in the process of cognition; it was the counterpart of a practical effort, and was “given” only in the context of that effort.’ The dialectic presumed for Marx was therefore the unity of theory and practice. Engels’ dialectic on the other hand, still stood under the influence of Charles Darwin’s discoveries, and one can safely state that he ‘Darwinized’ (and reformed) Marxism – although he thought that he was only preserving and supplementing Marx’ thought. Loyal to his lifetime friend, Engels thought he explained and clarified Marx’ thought as he did with his completion of Marx’ Capital.

Kautsky, Plekhanov, Luxemburg and the radical reformation of Lenin

After Engels’ death (in 1895) there were two tendencies in the social democracy of Germany, not only the birth place of Marx and Engels but also the country where social democracy was at its strongest in Europe. One was that Marxist orthodoxy was preserved by one of the two Marxist theoreticians, Karl Kautsky (1854-1938, image). In this context, the term ‘Marxist orthodoxy’ meant Marx’s thought as (re)formed by Engels. Kautsky stood in close contact with Engels in the last part of the latter’s life. Even more than Engels, Kautsky emphasized the ‘natural necessity’ of all social processes. Although aware of the differences between man and animals, Kautsky adopted a Darwinian view of history as a process resulting from chance mutations that permit the survival of the individual best adapted to its environment.

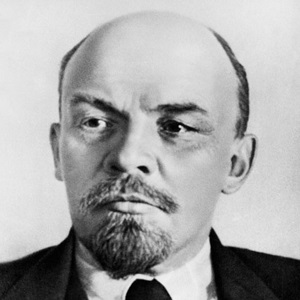

Following Engels, Kautsky took a naturalistic and positivistic view of society. However, whereas the inevitable socialist development could be studied scientifically, the revolutionary consciousness had to be inserted into the hearts and minds of the working class. In this respect Kautsky was on par with the Bolshevik leader Lenin, who thought that a minority of devoted revolutionaries had to influence the working class. Unlike Lenin (image), Kautsky was dismissive about the outcome of the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia in October 1917. A year after the Bolshevik coup Kautsky criticized the revolution because it suffered from democratic deficiency. Lenin, polemicist as he was, responded immediately with the brochure The Proletarian Revolution and the Renegade Kautsky, in which he attacked the German Social Democrat, stating among other things (and in doing so making a caricature of him), that Kautsky had turned his back on Marxism as he had forgotten that that every state apparatus is designed for the oppression of one class by the other. The Bolshevik government of Russia, so Lenin stated, was not just another governmental form but ‘a state of another type’.

Lenin’s attack deepened the gap between the two. In 1919 Kautsky even went further in his criticism, writing: ‘If the dictatorship of the proletariat is to be over-ridden by the dictatorship of its organisers, these in their turn will be over-ruled by the dictatorship of the tribunals.’ Apart from the content of the debate, it is interesting to note the use of the word ‘renegade’ by Lenin. Renegade means ‘apostate’, a term often used in Christianity to describe someone who loses faith. In communist terms as used a century ago it meant no less. Lenin pretended to be an orthodox Marxist and defended ‘his’ revolution as a Marxist one, although everything pointed out that the Russian Revolution was a break with Marx’ (and even Engels’) thought. Lenin can be described as one of the great reformers of Marxism, though pretending to be an orthodox and loyal follower of Marx’ thought.

Lenin grew up in a country where the dominating figure of Marxism was Georgi Plekhanov (1856-1918). Plekhanov (image) can be characterized as the Russian Karl Kautsky: he was an orthodox interpreter of Marxism, shedding light onto the Marxism that Friedrich Engels had given shape. This meant that Plekhanov also had a Darwinian view of history. In the specific Russian situation Plekhanov was an adherent of the orthodox vision that revolution could only come about when the proletariat was ‘ripe’ for revolution. It led him to the complicated reasoning that a bourgeois revolution was to be led by the proletariat. No wonder that the Russian Narodniki – fighting for the liberation of the peasant majority in Tsarist Russia and striving for an immediate revolution – saw nothing in this ideology.

This did not change Plekhanov’s status as Tsar of Russian Marxism. Among his admirers was Lenin, fourteen years his younger. As a ‘thinker’ (Lenin was never a theoretician, but as a thinker always a practical politician and a machiavellist) Lenin went through different phases: in his youth he was influenced by the Narodniki, as was his eldest brother Alexander (image). When Alexander was hanged after the failed assassination of Tsar Alexander in 1887, Lenin adhered to the new doctrine of Marxism as introduced by Plekhanov. But the young man (Lenin was 30 years old in 1900) soon developed his own ‘Marxism’. It was a combination of the voluntarism of the Narodniki and Marxist doctrine – but unlike this combination, a doctrine that had been interpreted in his own way.

Lenin reformed Marxism (and like Kautsky and Plekhanov he worked with the heritage Engels had wrought) in several ways. First of all, he no longer believed in the conviction that Russia was not ripe for Socialism, although the country, despite the reforms that had been introduced after the revolutionary year of 1905, was far from reaching the industrial state as required by Marxist doctrine. Secondly, Lenin was distrustful of the revolutionary consciousness of both workers and farmers. He wanted the Russian Social-Democratic party to be led by a small group of professional revolutionaries. As has been documented, these conflicting visions led to a split in the party in 1903, where the minority (Mensheviks) of the members present protested against Lenin’s agenda.

Lenin’s reforms would not be more than a footnote in (Marxist) history had there not been the coup of October 1917, which brought the majority (Bolsheviks) of the party of 1903 to power. Even in this early stage, Lenin was criticized for his far-reaching proposals that could end up as the dictatorship of a minority. In 1906, the Polish born communist Rosa Luxemburg (1871-1971, image) wrote ‘that the very idea of Socialism excludes minority rule’. She also criticized Lenin’s polemical and defensive book One Step Forward, Two Steps back that had been published in 1904. In this publication he not only commented on the minutes of the Party Congress of the previous year and gave his version of the split that had taken place, but reiterated his belief in the need of a narrowly-based party with at its core professional revolutionaries.

In imitation of the Mensheviks, Luxemburg accused Lenin of ‘Blanquism’, named after the nineteenth-century French Revolutionary Auguste Blanqui (1805-1881, image), who promoted the idea that a small group of ‘professional’ revolutionaries would take over power by a coup d’etat, assuming that the proletariat would support the coup. Lenin rejected the accusation that he steered towards ‘ultra-centralism’ in the party. He considered her polemic ‘a mockery of our congress, while abstractly and theoretically (…) it is nothing but a vulgarization of Marxism, a perversion of true Marxian Dialectics.’

True Marxian Dialectics…These sentences show that the Reformer Lenin wanted to create the impression that he was an orthodox Marxist and Luxemburg was not. However much he was convinced of his own orthodoxy, Lenin in fact used the same tactic as he did against Kautsky whom he accused of ‘renegarism’ of original Marxism. He made a headlong flight forwards with massive polemics in an attempt to silence criticism.

The firm opposition against the other great Reformer: Eduard Bernstein

The debate between Lenin on the one hand and Kautsky and Rosa Luxemburg on the other, was not the only debate about Marxist Reformation in the first decennium of the twentieth century. There was another one, in which the three were united against a man who gave voice to a trend that had been visible for some time in the late nineteenth century: Eduard Bernstein (1850-1932). Especially in England, where Bernstein lived for years, trade unions and political initiatives improved the situation of the working class. But it was Bernstein, well acquainted with both Marx, Engels and Kautsky, who systematized reformism in Die voraussetzungen des Sozialismus und die Aufgaben der Sozialdemokratie (1899). In 1964, more than thirty years after his death and more than a century after the publication of Evolutionary Socialism (the concise title of the English translation) Carlo Schmid, the then foreman of the West-German Socialist Party remarked: ‘Bernstein has triumphed across the board.’ Schmidt referred to the dominant role of the Social Democratic Parties in the creation of the Welfare State in Western Europe, which had improved the situation of the working class.

When it first appeared in 1899, Evolutionary Socialism was fiercely contested by the orthodox Marxists Kautsky and Luxemburg, who now found the other great reformer Lenin on their side. Little wonder that they did; Bernstein openly tried to adapt Marx’ thinking to modern times. And he rejected numerous dogmas that were common among Marxist intellectuals all over Europe at the turn of the century. Bernstein did not accept the theory of value such as had been expounded in Capital. Marx’ theory was ‘a speculative formula or scientific hypothesis’ without any basis in the real world. And although Bernstein believed that Marx’ statements concerning the falling rate of profit, overproduction, concentration and periodical destruction of capital were based on fact, he observed that Marx underestimated the contrary tendencies that were to be found in capitalism. Marx’ predictions of class polarization were erroneous in Bernstein’s view.

While Lenin pretended to rely on Marx in his reforms, Bernstein did not endeavor to show that he was faithful to Marx’ views. On the contrary, he wanted to keep the ‘positive’ elements of Marxism: his critic of capitalism and his attention for the position of the working class, but openly criticized the ‘negative’ element: the belief in speculative historical schemata and the pretention that that (Marxist) Socialism would be a complete break with the previous history of mankind.

It was for that reason that Marxists as divided as Kautsky, Luxemburg and Lenin fiercely attacked Bernstein. Shortly after the publication of Evolutionary Socialism, Rosa Luxemburg reacted with the brochure Social Reform or Revolution in which she pointed out, in opposition to Bernstein’s plea bring about Socialism through legal means, that ‘It is not true that socialism will arise automatically from the daily struggle of the working class. Socialism will be the consequence of (1), the growing contradictions of capitalist economy and (2), of the comprehension by the working class of the unavoidability of the suppression of these contradictions through a social transformation.’

For Lenin, Bernstein was one of the many revisionists. He put him on par with the social revolutionaries in Russia, who strived for the raising of the peasantry. Their amendments to Marx were ‘integral and fundamentally hostile to Marxism’. In his criticism Lenin apparently took an orthodox view, while he in reality – as discussed above – was one of the great reformers. That Lenin could continue as an orthodox Marxist can not only be attributed to the continued appeal of Marx’ and Engels’ writings. As Leszek Kolakowski has argued in Main Currents of Marxism, Marx and Engels formulated their historical materialism in ‘general formulas’ and these lent themselves well enough for the use Lenin made of them. Kolakowski went even further and stated that Lenin applied the principles of historical materialism more thoroughly than Marx. Kolakowski points to Marx’ thinking about law, which for Marx is nothing but a weapon in the class struggle. Kolakowski sharply concludes that it naturally follows that there is no essential difference between the rule of law and an arbitrary dictatorship.

Whatever the truth of the matter, in 1917 Lenin presented Marxism with a fait accompli. From now on Marxist thinkers were not only forced to think about orthodoxy and reformism in theory, but they also had to relate to Marxism in practice. As we have seen in the case of Karl Kautsky, that led to heated debates between himself and Lenin, and their debate was just one of many others that occurred. Other Marxist thinkers got involved in the debate as to whether the Russian state was a Marxist state or not. Between 1917 and 1989 roughly speaking three Marxist visions can be distinguished that concern ‘real existing Socialism’: some believed that the Soviet-Union was a (failed) attempt to implement Socialism in a retarded country; others (in the time of Stalinism and its aftermath between 1929 and 1968) qualified Soviet Communism as ‘state capitalism’ and yet others called it a degenerated workers’ state or the bureaucratic state.

Two ‘modern’ reformers: Antonio Gramcsi and Herbert Marcuse

Within the current context, it was important that with the growing criticism of ‘real existing Socialism’, that reformism became less and less taboo in Marxist circles, although of course all the reformist Marxists, each in his own way, returned to the patriarchs Marx and Engels. However, with the stagnation of the Russian Revolution and the absence of revolution elsewhere, there arose, though hesitantly, a cautious search for reforms in the interwar period. Proposals to this end came not only from Leon Trotsky (image), one of the leaders of the Russian Revolution who, since 1929, was exiled in several European countries before his emigration to Mexico in 1936, where he was murdered in 1940. Trotsky, as a critic of the revolution, ended up in an impossible position: his proposals to renew and consolidate the revolution (expropriation of the farmers and largescale industrialization) were implemented by his archenemy Stalin. All criticism was therefore stifled, all the more so as Trotsky in no way advocated a different, more democratic form of Socialism. He turned the full focus of his attention on the bureaucratic structure of the ‘Socialist Republic’, without really deviating from the Stalinist reality in Russia.

Trotsky became popular in the seventies of the twentieth century among a small group of intellectuals, but more as a symbol of the ‘alternative’ way the Russian Revolution could have gone. More influential in the seventies was the Italian Marxist Antonio Gramsci (1891-1937, image). The reason was not only his writings, but also his tragic life. Under Fascist rule he was put in prison in 1926 where he died in 1937, a few days before he was to be released. In prison he wrote almost three thousand pages, which later had an intoxicating effect on Marxist students in the seventies. That was not without reason as Gramsci turned out to be a reformator who would inspire students living in the highly developed welfare state and who were disappointed in the ‘real existing Socialism’ in the Eastern Bloc. Gramsci was a source of inspiration because of his theory of hegemony and his presumed topicality for society in the 1970s. Gramsci was one of the founders of the Italian Communist Party and himself less of a reformer than the left-wing students made of him. They ignored Gramsci’s attempts to ‘bolshewize’ the Italian Communist Party and emphasized his theory of ‘cultural hegemony’: Marxism should not be an economism but should fight for cultural hegemony to win the masses for their cause. This theory matched the efforts of the students in the seventies perfectly.

More or less comparable with Gramsci’s reputation as a reformator of Marxism is that of the philosopher Herbert Marcuse (1898-1979, image), who moved to the United States after the Nazis took power in Germany. Just like Gramsci, Marcuse became a hero of the students and intellectuals of the seventies, but whereas Gramsci (also isolated because of his imprisonment) lived in the evolving industrial society of Europe in the first half of the twentieth century, Marcuse, although raised during that time, was a Marxist critic of the highly developed welfare state in the second half of that century. Marcuse was part of the Frankfurter Schule, that company of German-Jewish scholars who combined the thinking of Marx and Freud. The members of the Frankfurter Schule were more sociologists than economists, and their ‘critical theory’, with its attention for the psychological discomfort in society, was in itself a reformation of Marxism, as Marx and Engels had mainly focused on economic traditions.

In a rather pessimistic analysis of Western society, Marcuse judged that it had encapsulated the working class. In Eros and Civilisation (1955) he wrote that the existing powers remained in place. But after the student protests in the sixties, Marcuse became (over) optimistic: he had high hopes that they would change society. But his Freudian approach towards society, a society full of rage and fury, and his elitist view of a small minority, raised the question whether Marcuse could be called a Marxist at all. Leszek Kolakowski, who meticulously charted all reforms within Marxism, stripped Marcuse of the label Marxist. According to Kolakowski, what Marcuse represents, is ‘Marxism without the proletariat (irrevocably corrupted by the welfare society), without history (as the vision of the future is not derived from a study of historical changes but from an intuition of true human nature), and without the cult of science; a Marxism furthermore, in which the value of liberated society resides in pleasure in pleasure and not in creative work. (…) Marcuse, in fact, is a prophet of semi-romantic anarchism in its most irrational form.’

The last attempt (Eurocommunism) and the real reformation

That’s how it was possible: the reforms Marcuse, who certainly considered himself a Marxist, proposed placed him outside the mainstream of Marxism. The same question can be posed about a completely different movement, which caused a brief furore during the same time (the seventies): Eurocommunism. It was another reaction to the crisis of Marxism and the ‘real existing Socialism’ that was ushered in by the destalinization speech delivered by the Soviet Party leader Nikita Krushchev (image) in February 1956 during the Twentieth Party Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. Kruschchev’s condemnation of Stalins ‘personality cult’ caused a shock in allied communist parties in both East and West. As an immediate result of the speech, a revolution broke out in Hungary. While the party strove to establish a desalinized form of Communism, a large part of the population wanted to get rid of it. The Soviet Union crushed the uprising, but the desire for reformation remained, as the Prague Spring proved in August 1968. After the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia, the Western communist parties tried to sail a more independent course of Moscow. Although hesitantly, and the one faster than the other, during the seventies, the communist parties of Italy, France and Spain set course for reformation.

The former Italian party leader Palmiro Togliatti (1893-1964, image), himself a hardliner during the time of Stalin, proclaimed after 1956 ‘polycentrism’: not all communist roads should lead to Moscow, each party had to go its own, national way. After him, the Italian communist party, especially under the leadership of Enrico Berlinquer, broke a taboo by breaking with Leninism, just as the Spanish communist party did in the seventies. Only the French communist party under the leadership of Georges Marchais remained ambiguous. While the party paid lip service to Eurocommunism, Marchais remained loyal to the Soviet Union. However, on March 5, 1977, in Madrid, the three parties proclaimed that they wanted to follow their own national way towards establishing a communist society, in accordance with the existing liberal institutions.

But this radical amendment of Marxism-Leninism was too little and came too late. It was too little because the Western European communist parties never really came to terms with the horrors of the Soviet regime. It can be called distinctive that the French communist historian Jean Elleinstein, the non-official spokesman of the Eurocommunist wing of the French communist party, attributed all crimes to Stalin (image), while carefully excluding Lenin from criticism. It came too late, because the communist alternative never convinced the electorate in Western Europe. This was a result of the bad example given by the ‘real existing Socialism’ in the East. Add to that the mistrust of the elite (and the United States), it meant that almost never (excluding France, where its involvement in 1981 resulted in disaster) did the communists share power, and it is clear that Communism never had a chance in Western Europe.

Therefore, if Western reformism in the form of Eurocommunism did not succeed, and ‘real existing Socialism’ after 1956 fossilized, and if reformation was a suspicious concept, where could reformation come from – if ever? History provides the answer: from above. The real reformation, in fact a second revolution as it has also been called , came from Michael Gorbachev (image), the leader of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union since 1985. But it was in line with more than a century of Marxist misunderstandings concerning the concept of reformation that Gorbachev fell back on Lenin to justify his reforms. However, he could not do anything else. Gorbachev was a convinced communist, who firmly believed in its founder Lenin and sincerely believed that his reform proposals were in line with Leninism. In practice there was no greater difference than between these two men. Lenin mistrusted the masses and deliberately founded an elite party to govern them. Gorbachev, raised in the Soviet system, gradually saw the slowness and even the inertia of the party and tried, as a true idealist, to reform the party by appealing to his dictatorial predecessor Lenin.

Conclusion

His six years of power were exciting and chaotic and lead to the demise of Soviet Communism in Russia and in the countries of Central Europe. But his unsuccessful reformation of Soviet Communism shows in a nutshell how difficult reformation was for the followers of Karl Marx. They could only openly declare that they wanted to reform, provided they legitimized this with an appeal to a predecessor, even though this predecessor thought something completely different. That it was difficult to reform Marxism openly appeared immediately after Marx’ death. Although Engels’ ‘Marxism’ differed from Marx’, he himself believed that he was merely an interpreter of his ideas.

Eduard Bernstein, who openly proposed a reform of Marxism, was treated as an outcast by Marxists such as Lenin, who himself was at least as great a reformer as Bernstein. Lenin was therefore attacked by Karl Kautsky, Plekhanov and Rosa Luxemburg, the self-appointed treasurers of Marxism, even though this Marxism was read through the eyes of Engels. After Bernstein, open reformism only came into vogue after 1956, when after the Stalinist terror had been unveiled, the bankruptcy of ‘the real Socialism’ became clear. Western Marxists such as Herbert Marcuse sought inspiration from other thinkers and were critical about the class on which the hope of Marxism had been established: the working class. But all attempts to achieve a democratic (Euro) communism were in vain. Reformation proved not only to be a loaded concept in Marxism, Marxism in practice could not be reformed and was, after the attempt of Gorbachev in Russia (the ‘Fatherland of Socialism’), doomed to ruin.