Alweer jaren geleden, om precies te zijn op woensdag 20 en donderdag 21 september 2017, vond aan de Vrije Universiteit een tweedaags congres plaats onder de titel From Reformation to Reformations. Naast de klassieke 16e-eeuwse Reformatie, die naast het katholicisme het protestantisme in het leven riep, werd ook aandacht besteed aan het begrip reformatie in andere levensbeschouwingen. Daarbij opperde ik het idee ook te kijken naar de rol die het begrip ‘reformatie’ in het marxisme heeft gespeeld, allereerst in het denken over Maarten Luther en de Reformatie. Omdat het een internationaal congres was spraken we onze referaten in het Engels uit, met de bedoeling dat referaat uit te werken tot een artikel, te zijner tijd te publiceren bij uitgeverij Brill. Te zijner tijd…dat kwam er nooit van, wel vaker een slechte gewoonte na afloop van wetenschappelijke congressen. Niet getreurd: ik plaats dit artikel nu op mijn website. In het Engels, zoals ik het destijds aanleverde. Voor wie het kan boeien: een artikel over marxistische reacties op de 16e-eeuwse Reformatie. Reacties van vooral Friedrich Engels en – eeuwen later – van leiders en ideologen van de Duitse Democratische Republiek (1949-1989), die de opstandige monnik uit de 16e eeuw als hun voorganger claimden.

Reformation was never an easy subject for Marxism. This becomes clear when one studies the respective verdicts on the religious Reformation of Marx, Engels and their successors such as existed in ‘real existing Socialism’ in the German Democratic Republic (1949-1989). It shows in a nutshell how later generations of Marxists struggled with the verdict of the patriarchs, especially Engels, who wrote extensively about the Reformation. How should one deal with the sixteenth-century religious Reformation, Martin Luther and the radical monk Thomas Müntzer (image)?

Marx, Engels and their struggle with Luther’s Reformation

That Marx and Engels reflected on Martin Luther (image) and the Reformation is not surprising. First of all, they were Germans and although they reflected on the political situation in, for example, England and France, they never neglected German history. Thinking about their country’s history almost automatically meant thinking back to Martin Luther and the Reformation, one of the most important milestones in German history.

In the early years of their careers, both Marx and Engels developed ideas about Luther and the Reformation. In 1844 (when he was just 26) Marx devoted some words to Luther in Zur Kritik der Hegelschen Rechtsphilosophie, an early and massive critique on religion that began with the famous words that critique of religion is the condition for all critique.

In Zur Kritik Karl Marx reflected on the strength and importance of theoretical criticism. A material force can simply be overthrown by another material force, but theory can grip the masses. And it is here that he brought up the Reformation and Martin Luther. He regarded the Reformation as the first phase of a revolution, a theoretical phase – beginning in the mind of a monk. Luther, who – in Marx’ view – overcame the bondage of devotion, replacing it with the bondage of conviction. Still, Luther’s ideas were progressive, so were those of Marx. Furthermore, in the typical Karl Marx style, he turned concepts upside down: Luther shattered faith in authority, restoring the authority of faith. Outer religion was replaced by inner religiosity, and where the body was liberated from chains, Luther enchained the heart. So, the Reformation went half way, not all the way. It was primarily a spiritual revolution, not a material one.

For Marx the Reformation went just half way to emancipating the people. In terms of historical materialism: sixteenth-century Germany was not ripe for the real revolution. Secondly: the revolution began in the mind of a monk, ‘now (Marx wrote in 1844) it begins in the mind of the philosopher’.

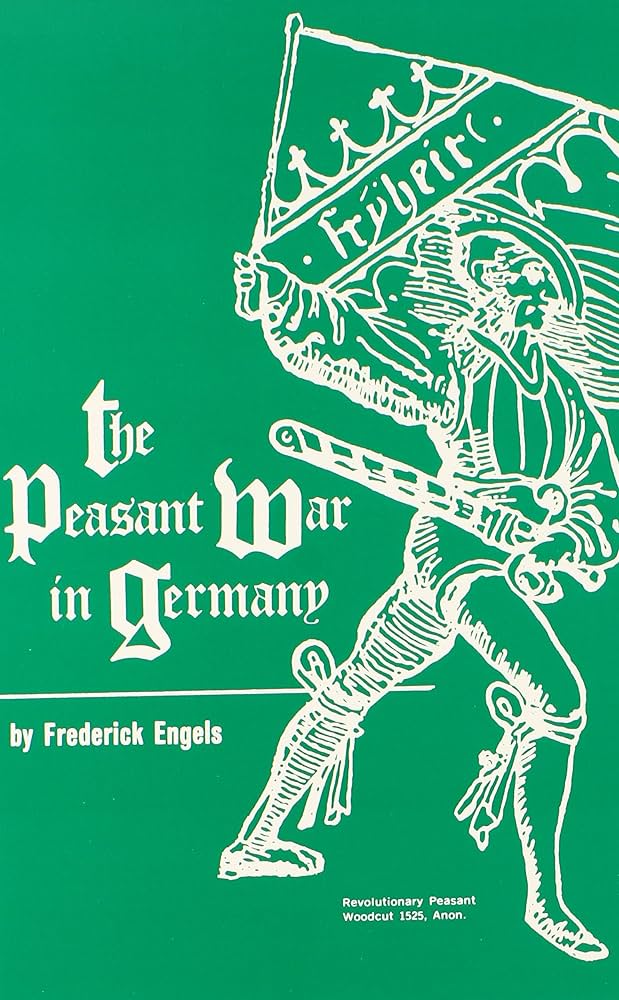

Frederick Engels took up Luther and the Reformation in the aftermath of the Year of Revolution, 1848. In the summer of 1850 he wrote The Peasant War in Germany, which appeared in the Neue Rheinische Zeitung, the political economic review edited by Marx. The book was written under the spell of the failed 1848 revolution. He looked for differences and similarities between the Reformation-period and the Revolutionary year of 1848. In the first edition of the book published in 1850 he wrote: ‘Who profited by the Revolution of 1525? The princes. Who profited by the Revolution of 1848? The big princes, Austria and Prussia. Behind the princes of 1525 there stood the lower middle-class of the cities, held chained by means of taxation. Behind the big princes of 1850, there stood the modern big bourgeoisie, quickly subjugating them by means of the State debt. Behind the big bourgeoisie stood the proletarians.’ In the reprint, published twenty years later, he wrote with a kind of self-criticism: ‘I am sorry to state that in this paragraph too much honor was given to the German bourgeoisie. True, it had the opportunity of “quickly subjugating” the monarchy by means of the State debt. Never did it avail itself of this opportunity.’

Meanwhile, no word on Luther in this preface and in the complement in 1874. Apparently, in the 1870s Luther and the Reformation had faded into the background. But by the mid-nineteenth century Luther had his full attention once more. Repeatedly Engels compared his advance in 1517 with the constitutionalists of 1848: Luther was overwhelmed by the radical Thomas Müntzer and the peasant movement, just as the constitutionalists were overwhelmed by radical democrats.

Engels distinguished phases in Luther’s career. In 1517, he first opposed the dogmas and organization of the Catholic Church. This caused a rebellion among all classes: peasants and plebeians, but also the bourgeoisie and the lower nobility were drawn into the torrent. Now Luther had to choose between the two. And he chose for the bourgeoisie and the lower nobility, and for his protégé, the Elector of Saxony. In the words of Engels: ‘He dropped the popular elements of the movement, and joined the train of the middle-class, the nobility and the princes. Appeals for war of extermination against Rome were heard no more. Luther was now preaching peaceful progress and passive resistance’.

For Engels (image) it was clear why Luther choose the side of the middle class. ‘The mass of the cities had joined the cause of moderate reform; the lower nobility had become more and more devoted to it; one section of the princes joined it, another vacillated. Success was almost certain at least in a large portion of Germany.’ When the Peasant War broke out, Luther tried to play a conciliatory role and criticized the governments as well as the revolters, who were ‘ungodly’ and acted against the Gospel.

The real revolutionaries were led by Luther’s opponent Thomas Müntzer, who, like Luther was a theologian. In his highly romantic and anachronistic view of Müntzer, Engels regarded him as a precursor of Humanism and Atheism and more than that: as an early Communist. His end is well known: Müntzer was decapitated in 1525, Luther died more than twenty years later. Engels regarded the princes as the winners of the Peasant War and compared their fate with the radicals of 1848, who were also defeated, in their case by the bourgeoisie.

Engels’ view was recently criticized by Paul R. Hinlicky (image), a professor of Theology at the Lutheran Roanoke College in Virginia, the United States. To Hinlicky, Engels ‘constructed a parallelism between the historical Müntzer–Luther relationship and his own 19th-century polemics against rival socialistreformers from his more radical stance of revolution.’ The weak point in Hinlicky’s analysis is, however, that he only takes The Peasant War in Germany into consideration. As the Dutch historian Jan Herman Brinks has proved, Engels’ verdict on Luther and the Reformation was more positive. The Reformation – the Lutheran form as well as the Calvinist – contributed to undermining the monarchy and was a popular expression of the proceedings at that time. In 1892, three years before he died, Engels once more reflected on the role of the Reformation and concluded that where Luther failed, Calvin succeeded. ‘Calvin’s church constitution of God was republicanized, could the kingdoms of this world remain subject to monarchs, bishops, and lords? While German Lutheranism became a willing tool in the hands of princes, Calvinism founded a republic in Holland, and active republican parties were to be found in England, and, above all, in Scotland.’

Whereas Engels reflected on Luther and the Reformation throughout his life, Marx focused less on Luther. But when he did, he remained moderately positive about the man of the Reformation, especially in Das Kapital (1867) where Luther, living in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, is described as a critic of mercantilism. Marx appreciated Luther’s analysis of the changed role of money in that period, which had led to usury.

To summarize: both Marx and Engels were critical of Luther, though the three had something in common: the Atheists as well as the men of the Reformation were, in their own way, apocalyptic thinkers and severe critics of their time.

The German Democratic Republic, Luther and the Peasant War

So far for Marx and Engels on Luther. But it didn’t end there. There is a postscript in the twentieth century in the form of the German Democratic Republic, the so-called ‘first socialist state on German soil’ (1949-1990). It was here, in the eastern part of Germany, that Luther was born: in Eisleben. And it was here, where he published his famous theses against indulgences: in Wittenberg. How did that state look back on Luther?

Immediately after the Second World War, Luther’s reputation was damaged. Communist party-officials drew a straight line between Luther and Hitler. Even before the foundation of the GDR, during the period of the Sozialistische Besatzungzone (1945-1949), Alexander Abusch, later the Minister of Culture in the GDR, quoted the nineteenth-century German critic Ludwig Börne (image) who in 1830 wrote: ‘The reformation was the tuberculosis which caused the death of German freedom, and Luther was the gravedigger’. It leads Abusch to conclude: ‘The defeat of German freedom in the Great Peasants’ War enveloped three centuries of German history in reactionary darkness’.

But a few years later, during a conference in Berlin in 1952, Kurt Hager, later the chief ideologist of the SED, already had a slightly different view on Luther. Luther was now not only the creator of ‘a unifying bond’ between the Germans, his advance also marked the decline of feudalism and the creation of a German national consciousness. But throughout the 1950s and 1960s, there was much more interest in Thomas Müntzer, the revolutionary and suppressed hero of the Peasant War.

That changed in the run-up to the ‘Luther-year’ of 1967, though only reluctantly. Before 1960 Luther, Müntzer and the Peasant War were regarded within the context of German history and seen through the lens of historical materialism: the Peasant War, and especially Müntzer, were seen as proofs that Germany had experienced a revolution – this was more or less in line with Engels’ book The Peasant War.

Since the 1960s the focus remained on Müntzer and the Peasant War but much more attention was paid to Luther and the Reformation. GDR-historians were allowed to conclude that Luther and Müntzer, however hard their fight, seen historically, belonged together. The commemoration of 1967 gave the GDR an opportunity to show itself through Luther as the ‘better country’. The commemoration of 1967 thus marked a cautious rehabilitation of Luther.

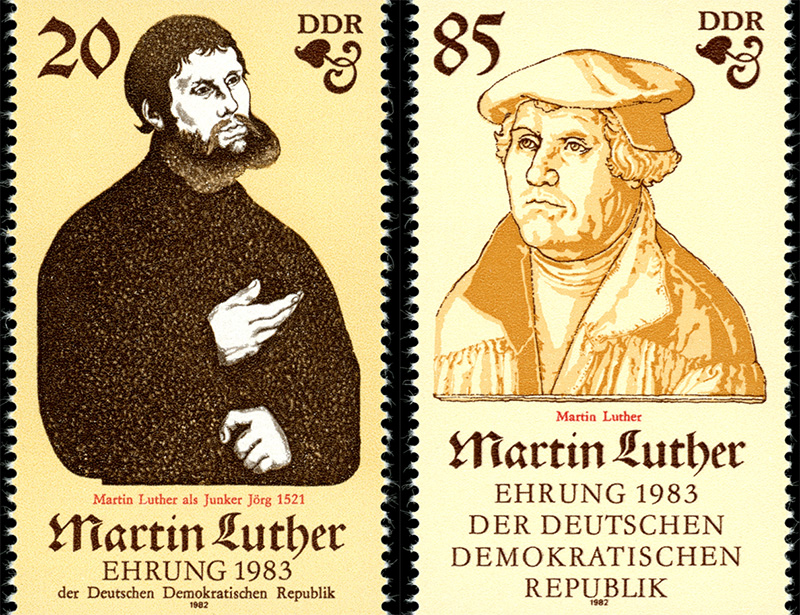

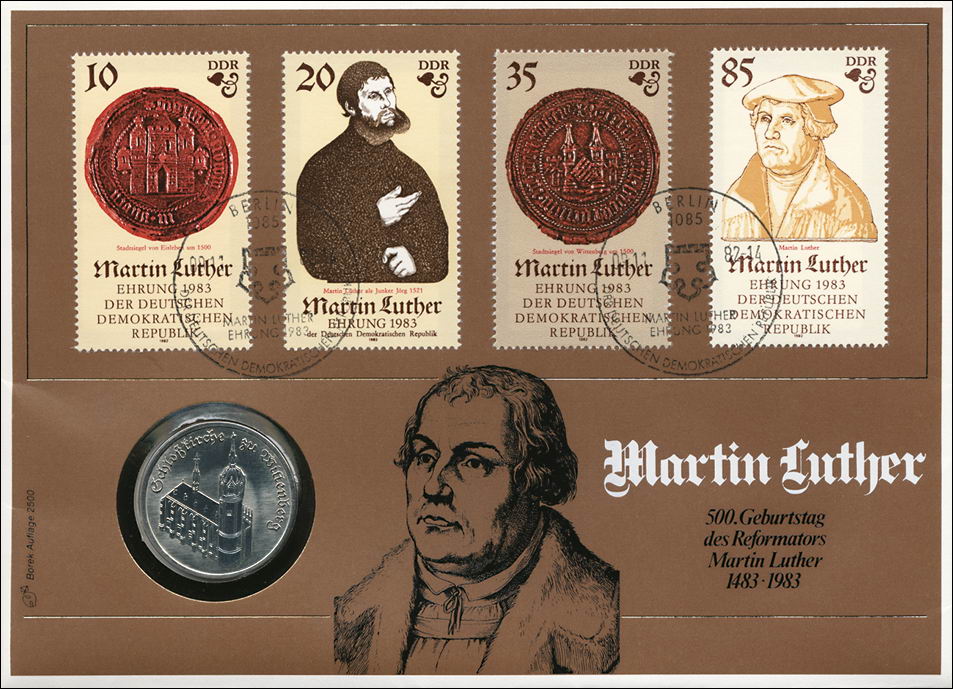

A more open rehabilitation could be seen in 1983, although it was a rehabilitation born out of necessity on the part of the Communist Party. In her search for legitimacy, the Party once again recalled Martin Luther, who had been born 500 years before. As if to underline the importance of the commemoration, as early as 1980 a committee was formed under the presidency of the president and party leader Erich Honecker.

On that occasion Honecker emphasized that Luther was one of the great sons of Germany, even a giant in his time. But he had never foreseen that his reformation would end up in revolution. The words were well chosen: now Luther was no longer firmly attacked as having obstructed Thomas Müntzer’s revolution. On the contrary, the visions of Luther and Müntzer were more or less harmonized. The vision now was that the Reformation was the first revolutionary Turbulence on German soil.

As a result, in 1983 there was more room for Luther’s theology. He was memorialized by the Evangelische Landeskirche as the man who taught that man was a beggar, dependent on the grace of God – something completely different than the Promethean vision of Marx and Engels, who taught that (proletarian) men should break their chains. The GDR-leadership let it be, realizing that the Church was an important institute, which they should not alienate. The irony of this history is that the Church functioned as the prime patron of the regime-critics in 1989. Ironically, one can say that Luther had won the battle with the crippled heirs of Marx and Engels, who were the real revolutionaries, and who broke up the status quo of a brutal dictatorship.

To conclude this part, one can say that the history of more than a century of Marxist interpretations of Luther and the Reformation not only showed a variety of opinions, beginning with those of Marx and Engels, but also showed in a nutshell the decline of the power of Socialism in the twentieth century. Engels and Marx differed slightly in their opinion of Luther and the Reformation, but their verdicts were those of two German revolutionaries, living in the nineteenth century and not bothered by the need to hold power. For both Marx and Engels, Luther was a willy-nilly revolutionary. Engels, in his The Peasant War in Germany, judged Luther more harshly, as it was he who chose sides with the princes and helped to crush Thomas Müntzer’s revolution. The later Marx, writer of Capital, appreciated Luther as a critic of mercantilism and usury.

Just as bluntly as Marx and Engels judged Luther and the Reformation, so politically motivated were the respective verdicts in the GDR. From the very start, the state Socialism in the eastern part of the divided Germany had had a problem with its legitimacy. Luther and the Reformation offered both an opportunity and a problem for the state. The opportunity was that he was the catalyst of the Turbulence in early modern Germany. The problem was what to do with his orthodox theology?

Until the 1980s, Luther’s theology was mostly ignored and orthodox Marxist interpretations prevailed, long inspired by Engels’ rejection of Luther. In 1983, under pressure of the decreasing support of the people, there was more need than ever to promote Luther as the ancestor of the East German state. Even Luther’s theology could now, albeit with some party-limitations, be discussed. The party did not allow it wholeheartedly but did so with a clever instinct for power. It was not enough: the Socialist state disappeared abruptly and is now almost forgotten, while Luther and the Reformation are still being discussed.