Op 8 april 2014 gaf ik een lezing in de serie ‘Slavic Delights’ van de afdeling Slavische studies van de Universiteit van Amsterdam. Die avond had als titel ‘Jan Karski. Humanity’s Hero’. Prof. Ellen Rutten, hoofd van het departement Slavische studies, leidde de bijeenkomst in, waarna ambassadeur Jan Borkowski sprak. Iwona Gusċ, als historica verbonden aan het Niod, sprak over Karski als oorlogsheld en boodschapper in transnationaal perspectief. Ik sprak over Jan Karski de politicoloog, die na zijn poging de Amerikanen er tijdens de oorlog van te overtuigen dat er een massamoord op de Joden gaande was, in de Verenigde Staten bleef. Hij moest met lede ogen aanzien hoe Polen werd onderworpen en onderdrukt door de Sovjet-Unie na te zijn verraden door het Westen. De voertaal van deze internationale bijeenkomst was Engels, vandaar dat ik deze lezing hier ook in de taal afdruk waarin ik die uitsprak.

There is something strange in the case of Jan Karski (photo). At least in Western Europe and in the United States of America. Remembering Karski is first of all remembering the eye-witness of the Holocaust, the man who as one of the first contemporaries spoke about the Holocaust. The story is well known: between 1977 and 1985 Karski was rediscovered by a number of intellectuals who made study of the Holocaust. Among them the famous British historian Walter Laqueur, who gave a sharp but brief picture of Karski’s report to the Western leaders about the atrocities in the nazi-concentration camps in his book The Terrible Secret. Furthermore Elie Wiesel, the later winner of the Nobel Peace Price, who took notice of Karski and asked for more interest in his remarkable appearance and personality. Filmdirector Claude Lanzmann did the rest. He interviewed Karski in his classic film Shoah, although Karki was not entirely satisfied with his role in it.

Let us look closer: what does this exclusive attention on Jan Karski as messenger of the Holocaust mean? In my opinion it means two things.

First of all there can be noticed that something fundamentally has changed in the historiography of the Second World War. Certainly, before the 1960ties there was attention for the murder on the Jews. One can think about the book The Final Solution of the British Historian Gerald Reitlinger, which was published in 1953. But this was a pioneering study of the Holocaust at a time when books about the war were dedicated to the orgins and consequences of the war, which was described in diplomatic and military terms. One can think of books from the German historian Walther Hofer (Die Entfesselung des Zweiten Weltkriegs) or of the highly controversial study The origins of the Second World War from the British Historian A.J.P. Taylor.

As the Dutch Historian Hermann von der Dunk has remarked: after the sixties the murder on the jews became more and more in the center of the historiography of the Second World War. And – in the slipstream of that historiography also in the center of attention from the public opinion. That’s the first reason why we hardly talk about the rest of Story of a Secret state, Karski’s book which, in Dutch translation, tells almost 400 pages. Only a few chapters are devoted to his “visit” to the concentration camp, the rest of the book deals with the Polish underground army and the underground Polish State under the German Occupation. Still, since the Holocaust is in the center of the attention of the World as the unique “crime of the century” there is less interest in the rest of the book. Sometimes it seems that the book deals only with of the fate of the Jews and not also with the fate of the Polish People.

That marks my second point: only recently there is real interest in the fate of Eastern Europe and especially in the fate of Poland. In the years that Jan Karski was “rediscovered” (the seventies and eighties of the previous century) the Soviet Union regained in Western Europe a reputation as victor of the Second World War. Regained…because that reputation was badly damaged in the coldest years of the Cold War. The liberals, Christian Democrats and especially the Social Democrats were fiercely anticommunist over the years 1947-1970.

After that time a new generation stood up. In the Netherlands but also in countries like France and the United States students and other intellectuals were suspectible to new forms of marxism. They were not in a simple way fellowtravellers of the Soviet Union. But they had an easy and comfortable image of The Second World War in Europe. It sounded like this: The Second World War was a war of the the three Allies the United States, Great Britain and the Soviet Union against The Third Reich. The Allies all three had an equal good reputation as liberators after the war as the destroyers of the undisputable evil of the nazi’s. The Soviets moreover lost 27 million people and had therefore in the seventies and eighties the sympathy of a great minority of leftists in Western Europe as the true victor of the war, namely the victor who had won at all costs.

The supremacy of the Allies was demonstrated at the trial of Nuremberg where most of the nazi-leaders werd condemned to death. How strange: one of the Allies was a regime as criminal as the Nazi-regime: that of Stalin. The Stalinist regime not only fought a war against his own people, as the respected historian Nikolas Werth has stated in the French classic The Black Book of Communism, but also against conquered peoples in the Second World War.

The history is wel known. Who is not familiar with this history can read about it in Karksi’s Story of a Secret State. Karski lively writes about the Russian invasion on the 17th september of 1939 and the drama that followed. That drama – the notorious murder of about 20.000 officers of the Polish Army in the spring of 1940 – was taboo in Nuremberg. No wonder: the Soviet prosecutor at the trial, Iona Nikisjenko, was in the thirties highly involved in the crimes of the Stalinist regime. Therefore: how could a regime that rivaled in bloodthirst with the nazi-regime be the obvious judge in Nuremberg? The answer is as simple as it is cynical: as far the Soviet-part in the judgement is concerned it was victory judgment. For once nazi-leader Hermann Göring was right.

Meanwhile: Jan Karski, we can read in his Story of a Secret State, narrowly escaped the tragic fate of his fellow officers in Katyn. Was he murdered, we had never heard of him. And we had never heard about his message to the world about the Holocaust. And, last but not least, we had never heard of his struggle for a free and independent Poland, free from totalitarian rule and oppression which especially in the stalinist years was hardly to bear as Anne Applebaum brilliantly described in her book Iron Curtain. The Crushing of Eastern Europe 1944-1956. But the oppression didn’t disappear in the years after the destalinisation-speech of Nikita Kruschev, although the totalitarian grip on Poland, the most difficult country in the Warsaw pact in the eyes of the Soviets, loosened – especially in the 1970’s and eighties.

But the great question was and is: will we listen to this other story of Jan Karski? The story of Poland in the twentieth century which was – not for the first time in history – playball of the great powers. In 1944, when Karski wrote his Story of a Secret State the American Publisher refused Karski’s chapters on the communist occupation and oppression. In the light of president Roosevelts appeasementpolitics towards Stalin that can’t be a surprise. Roosevelt wanted a strong United Nations and was under the impression of the charming “Uncle Joe”, who misled him as well as many others.

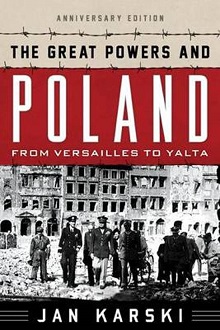

That was painful for Jan Karski, who stayed behind in the United States and obtained its citizenship in 1954. In 1985, the year in which he obtained fame by his appearance in the film Shoah, Karski published his masterpiece The Great Powers and Poland. From Versailles to Yalta. 1919-1945. The impressive, thorougly researched study was the result of years of thinking about the fate of his homeland in which this fiercely anticommunist man wasn’t welcome as long as the communists stayed in power.

Although The Great Powers and Poland was highly estimated by intellectuals as the former security adviser of president Carter, Zbignew Brezinski, himself – as Karski – not only from Polish origin but also a convinced anticommunist – the book never draw the attention like Story of a Secret State. One can imagine the reason for that: whereas Story of a Secret State is a personal, sometimes exciting document, The Great Powers and Poland is rather a dry diplomatic study of international relations. Nevertheless, when we look closer we do not only see the skills of the political scientist Jan Karski, a life long professor at Georgetown University in Washington, but also his own opinions of the fate of Poland in the twentieth Century.

What were these opinions? Karski (photo) wouldn’t like the word “opinions”. His book, he stressed in the preface of The Great Powers and Poland, has (I quote here) ‘not been structured as to convey any message or judgement’. The book was based on thoroughly researched archives, memoirs of the main statesmen and studies of other scholars. But everyone who reads the book between the lines, remarks the drama of Polish history that effected Karski personally. At the beginning of the book Karski writes in a distant manner that between the two World Wars the Poles were only once able to determine their own fate by themselves. That moment was during the Polish-Bolshevik war of 1919-1920, where the troops of Jozef Pilsudsky hold out against Lenins attempt to try to spread the communist revolution throughout Europe.

The ‘wonder of the Wisla’ had lasting and grave consequenses for Poland, as more than one biographer of Josef Stalin has pointed out. The Russian-Polish war not only led to the first quarrels between Leo Trotski (photo) and Josef Stalin. Trotski, the great man behind the Red Army, reproached Stalin that he gave bad directions to his staff in the Polish fields. It is said – for example by the British historian Adam Zamoyski – that Stalin hated the Poles since his defeat in 1920. The price would be high: in the Great Terror hundreds of Polish communists werd murdered bij the Stalinist regime or disappeared in the Gulag.

Meanwhile, what a terrible statement Jan Karski had to make: the victory against the Bosheviks as the one and only moment between the two wars that Poland could decide about its own fate… Soon after the First World War, the West, in particular France and the United States, stood positive against the Polish aspirations, who wanted to lead an national life with national selfgovernment. In the war Poland had been a playball between the Central Powers (The Austian-Hongarian monarchy and the Germany of Kaiser Wilhelm) and Tsarist Russia. But thanks to the help of the American President Wilson, who in Versailles advocated the Polish cause, in 1919 there emerged an independent Poland.

But from the start the independence of Poland was threathened. Not only by the bolsheviks in 1920, but also by the German-Russian alliance after the First World War. General Groener (photo), an influential member of the postwar cabinet, wrote in 1922 that (I quote here) ‘Poland’s existence is intolerable and incompatible with Germany’s vital interests. Poland must disappear, and will disappear through its own weakness and through Russia with our aid’. Words were followed by actions: in 1922 Russia and Germany made the Rapallo-agreement which gave advantage to both the Reichswehr and the Red Army. The key problem for the semi-democratic governments in the Weimar Republic remained the lost territories in the East, especially Danzig, the “freestate” under the League of Nations.

The Nazi’s added poison to general distrust of Poland: racial hate. Karski writes in detail about the negociations of the Soviets and the nazi’s in the eve of the Seond World War. The Soviets wanted to stay out of the conflict between the “capitalist” societies. After signing the Molotov-Ribbentrop agreement (photo) in august 1939 foreign minister Molotov cynically remarked: “We shall see what fighting stuff they are made of”.

After the German invasion the nazi’s not only destroyed Poland from the European map, but they also tried to rule out the intellectuel elite of the country, just as Stalin did after the Sovietinvasion with the military estabishment. Not in his diplomatic study The Great Powers and Poland but in Story of a secret state Jan Karski gave a sharp and personal picture about the German discrimination of the Polish People during the war.

The Second World War can here further be left out of consideration. We have only to remark this: with exception of the Russians and the Jews no nation lost so many people as Poland. And the suffering was not over in 1944. The “liberation” of Poland by the Red Army meant a new occupation, one which lasted for over forty years. Sober Karski describes the fate of Poland in Yalta (photo). In military terms Great Britain and de United States had to deal with the accomplished fact that the Red Army had reached Warsaw and further. What to do? Churchill, who had made all sorts of promises to help the Polish People, was in fact already during the war forced to give in to Stalin.

During the Conference of Teheran in 1943 Churchill agreed with Stalin that Poland should obtain compensation of the loss of the Eastern parts to the Soviet Union in the form of Western parts of Germany. That’s exactly what happened. Poland moved up to the West and lies still there. The British and Americans put pressure on their Polish Allies in England to recognize the puppet-government in Warsaw. The most important man on the polish site after the death of general Sikorski (photo), Stanislaw Mikolayjczyk, had to give in and took part in the elections in january 1947. Needles to say that these elections were far from free. The communists, who terrorized their opponents, won with an overwhelming and more than doubtful majority.

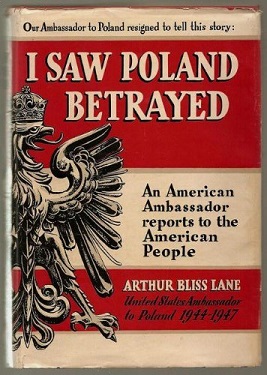

Jan Karski ended his detailed diplomatic study with two booktitles. He calls into rembererance that Mikolayjczyk wrote a memoir under the significant title The rape of Poland. And he reminds of the booktitle of the American Ambassador in Poland Arthur Bliss Lane, who gave his chronicle of events the title I saw Poland betrayed. Karski himself was too much a gentleman and scientist to say this in his own words. But his message was clear: Poland was raped by the Soviet-Union and betrayed by the Western Allies. This was the second message of Jan Karski, the message that never reached the same popularity in the West as his message about the Holocaust. And still this message was of equal importance as that about the Holocaust.

Why didn’t we listen to this message? I have already pointed out some reasons: the status of the Soviet Union as one of the victors of the War, the leftist movement in Western Europe and in the Netherlands in the 1970s and 1980’s. There is another reason: general indifference to and lack of knowledge of the countries of Eastern Europe. We, in the Netherlands, were mainly interested in North-America. Loved or hated: after 1945, the United States was our horizon. We were transatlantic and looked up to the United States with our back to Eastern Europe. Its time to turn now to countries like Poland which always belonged tot the European familiy and is now moreover a fierce and firm partner of the European Union.

Let us listen to this second message of Jan Karski, who saw his country betrayed in the twentieth century. The responsibility for vulnerable countries, playball of the great powers, is not just history. This responsibility is here and now, as the crisis in Ukrain shows day by day. Jan Karskis “second message” is therefore not just a historic message. It is a actual message.